This post is about something people sometimes think it isn’t polite or professional to talk about: money. I’ll confess that I’m a little nervous to post it because it shares some personal details about the money I received to write my second book. But, since my mission at Manuscript Works is to demystify the publishing process for scholarly authors, I feel that we’ve got to talk about this aspect of it too.

I asked Kate McKean, literary agent and 20-year veteran of the publishing industry, if she would join me for a chat about book royalties. If you’re curious about how trade publishing works, Kate’s newsletter and archives are must-reads. (She’s also working on a book of her own about writing and publishing books.)

We decided to structure our conversation as a tour through my last royalty statement for The Book Proposal Book. If you’re new here, here’s a quick recap: The Book Proposal Book was published by Princeton University Press in July of 2021 in their newly launched Skills for Scholars series. I submitted a proposal for the book in July of 2019, went through peer review of the proposal and sample chapter in the fall and was offered an advance contract, which I signed in January of 2020 (after some negotiation). The full manuscript was peer reviewed and accepted for publication six months later. I thought reviewing my own royalty statement might be helpful for any authors out there who want a preview of what they can expect after their book is published or who need some help interpreting a royalty statement they’ve already received.

First, a caveat about comparison. I’m sharing real numbers about my advance and royalties, because I think real numbers make everything easier to understand. But I strongly discourage you from using my numbers as some kind of baseline or typical representation of scholarly publishing as a whole. Every book has its own audience and market, and how-to books are a lot different from research monographs.

Publishers make calculations about expected sales and losses for each book based on all sorts of factors, so what they think is a fair deal for one book will not necessarily correlate to the deal they offer another book (even books by the same author). Conditions change in the world and within the press, so a deal made years ago might not be made the same way tomorrow. Deals are also affected by how many presses are competing to land the same book.

I’m saying all this because if you’ve had a book published, I don’t think it will be particularly useful to compare your specific numbers to mine, and if you haven’t had a book published yet, please don’t go and take my numbers to a press and say they should match them because this is what Laura Portwood-Stacer got for The Book Proposal Book. That won’t help anybody (including you).

Ok, now that that’s out of the way, let’s dive in!

Laura: Hi Kate! Thank you for joining me today. First, let’s get some basic terms down. What are royalties and what is an advance?

Kate: An advance is the money a publisher pays you up front to write the book when you sign a contract with them. And it’s an advance on your future earnings. They are saying, “this is the amount of money we are willing to front you, and you don’t have to pay any of it back,” because you don’t have to pay an advance back. After your book earns that amount in sales, then you will get royalties, which is a percentage of sales that is defined in your contract. Royalty percentage amounts can be different for every book.

Laura: Great. So let’s start at the top of my royalty statement here. And maybe we should talk about the dates it covers — a whole year from July 2021 to June 2022. I receive a statement and payment once a year. I tried to ask for twice a year (on the advice of a lawyer from the Authors Guild), but the publisher said no.

Kate: You will almost never get to negotiate the royalty pay-out structure because they typically do it at the same time across the board with some software system.

Laura: Good to know. So this statement is from the period of July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022. My book was released on July 13, 2021, so this is almost the entire first year of sales but not including most of the preorders, which were on my previous statement.

Kate: Yeah, once you’re in the system, you may receive a royalty statement even before your book is published. If you don’t have any preorders yet, the numbers might all be zero.

Laura: Ok, so let’s start with the balance brought forward from previous statement. That number, -$8,692, is slightly less than my advance of $10,000. And I should say that my press arranged for my index and charged that against royalties too, so my total “advance” was closer to $11,000.

Kate: Good. Having the press charge the index against royalties is something I as an agent would always try to work into a contract, so the author is not paying out of pocket for that. So that number, $8,692, is all the money you hadn’t earned out yet at the beginning of this statement period. You would need to earn that amount in sales in order to fill your advance pot and start receiving royalty payments.

Moving on to Earnings Accounted this Royalty Period, this is all the different ways you earn money on book sales. You have all the different formats here with their own ISBN number: paperback, hardback, and ebook. The audiobook isn’t in there because your publisher licensed the audio to somebody else.

Laura: Yes, I received a lump sum for the audiobook and that appeared on the previous year’s statement.

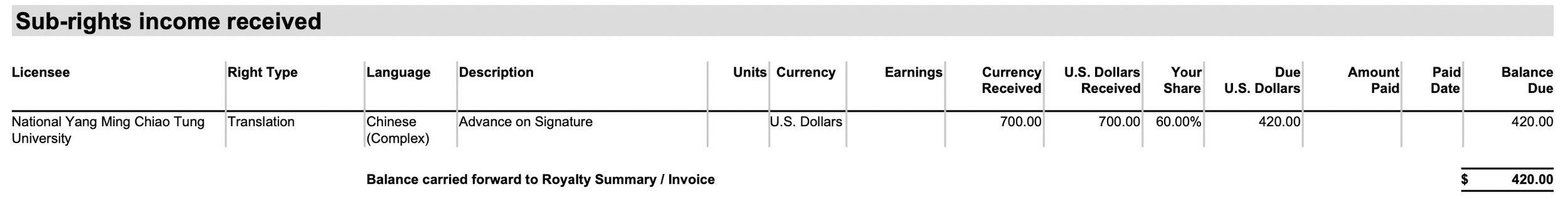

Kate: And then Subsidiary Rights. It says to see the Subsidiary Rights Statement for details, so we’ll get to that in a minute, but here it shows the share you received of whatever the press sold those rights for this year.

Moving down to balance due carried forward to remittance advice, that’s the total amount they are going to pay you. Remittance advice is essentially the invoice for the check they’re going to be sending you, assuming the balance is high enough.

Let’s check that math, just to make sure the numbers are right. A lot of how we figure out what a royalty statement is saying is to actually crunch the numbers, to be like “oh yeah, that number is equal to those numbers subtracted from that number,” because the statement doesn’t always show the work, you know? So sometimes we just pull out the trusty calculator.

So the first page is a complete summary of everything that’s going to come later in the statement. That’s nice to have because sometimes presses don’t summarize it like this on the first page and you have to go through and total everything up page by page. Here it shows the balance forward (-$8,692) plus the earnings from sales of the three formats ($9,869) plus your subsidiary rights earnings ($420) for a total of $1,597. The numbers we are going to see on the later pages of the statement are all included here, so this is the total to be paying attention to.

This total should match the check you got from the press. Sometimes, you don’t even know where the numbers come from, you’ll just get a check and it’s not the same amount as on the statement. So you have to figure out if they messed something up or if there’s something not showing up in the statement.

This statement is also nice because it has a little box showing the units and earnings for the current period and the cumulative units and earnings. Not all publishers show that and it’s very frustrating. As an agent, these are the numbers I would be looking for when I receive a royalty statement on behalf of my author. This is what the author is going to want to know — how many copies sold and how much money are they due?

Laura: Ok, so this total being a positive number means I made it. I get a check, which means I’ve earned out the advance.

Kate: That’s correct. Congratulations, that’s fantastic, and to do it in a year is amazing.

Laura: Thank you! I was shocked, personally. Moving on to the page where the paperback numbers are broken down, I thought this would be a good place to talk about royalties in more detail.

Kate: Yes, so broadly speaking, you earn a different royalty rate depending on the discount the publisher put on your book when they sold it to different retailers, as well as different royalty rates for different formats, too (paperback vs. ebook, etc.). A standard bookstore discount rate would be about 50-ish percent off the list price, but every book and every publisher will be different. In some cases, the publisher puts an even higher discount on the book and you get a lower royalty on those sales so that the publisher doesn’t lose money.

If your contract says your royalties are on net receipts, the amount you receive will be lower than if you got royalties on the list price of your book. Net receipts means the retail price the customer paid minus the publishers’ cost, which includes the discount given to the retailer. By doing some math based on the numbers in this statement, we can see that the average net receipt for your paperback was about $12 versus the list price of $20. So your royalties started at 10% of $12.

Laura: Yes, royalties on net receipts are the much more common arrangement in scholarly publishing. So I made about $1.20 on each book at that royalty rate.

I thought this might be a good time to talk about escalators, since we can see that there are different royalty rates here for the US paperback.

Kate: Yeah. So what they offered you — or what you negotiated — is for the first 3,000 copies of the book sold, you got 10% of net receipts. Then from 3,000 to 6,000 copies, you get 12.5%.

This statement shows about 1500 copies sold at the 10% rate, so you must have had about 1500 copies on your previous statement.

Laura: Yes, those were the preorders.

Kate: Got it. So your next statement will probably show zero copies sold at that rate because you’ve already filled that pot and are now earning 12.5% on new copies sold.

Laura: Yes, and once I hit 6,000 copies, there’s another escalator to 15%. These escalators were something I negotiated when I got the offer.

Kate: Oh, that’s great. And the 15% rate isn’t shown here because you haven’t gotten to it yet.

Laura: Right.

Kate: Five-thousand, ten-thousand, and fifteen-thousand copies are pretty standard escalators, at least in fiction. So you did a good job getting that down a little bit.

Laura: Can you tell us what refund of retained income means?

Kate: That is likely the reserve against returns that they did not pay you on your last statement. When a publisher sells a stack of books to a retailer, the retailer is allowed to return them to the publisher if customers don’t buy them. The publisher has to give that money back to the retailer, so they often hold some back from the author for a while in case there are returns. The publisher doesn’t want to have to come ask you to give your royalties back if your books get returned by a store, so they keep this little cushion in reserve. It’s 100% normal for returns to happen in the life of a book.

The way the publishers hold this reserve and pay it out to you will be specified in your contract. Sometimes that language can be negotiated so the publisher can’t hold it for more than two years, or something like that.

Laura: I think the hardback royalties are pretty straightforward to interpret, because there are no escalators on those copies.

Kate: That’s interesting, I missed that at first. In trade publishing, royalty escalators are more likely to be on the hardcover than on the paperback.

Laura: This might be an academic publishing thing. Hardcovers are often priced at $100 and sold to university libraries. The paperback is where you’re going to try to sell the most copies via retail.

I just want to pause to look at the ebook for a second, because this was a royalty rate I negotiated up quite a bit when I got the contract, and it paid off.

Kate: A lot, yeah. What did they offer you at first, do you remember?

Laura: I think it was around ten or fifteen percent but I got it up to 25%.

Kate: 25% is industry standard now. As an agent for trade books I would never take less than that. But a lower rate might be more standard at university presses.

Laura: Ok, let’s talk about subsidiary rights. I imagine this is the thing my readers will know the least about.

Kate: Yes. So it looks like the sub rights department at your press sold the translation rights in complex Chinese, which is fantastic.

When you signed your contract, you gave your publisher a package of rights that they get to try to sell. You gave them those rights because you weren’t going to try to sell them on your own. You probably gave them translation rights and English rights throughout the world. So that means the publisher has the right to license their English language edition to other publishers who publish in English. This could be publishers in France who sell books to people in France who speak English and also publishers in other countries where English is widely spoken, like Australia and the Philippines. This is different than English copies that your publisher ships overseas; those are exports.

Your publisher can also work with foreign publishers to translate the book into languages other than English. This is what they did here. It looks like your publisher received $700 for the translation, which is pretty normal. And then you get 60% of that, based on what you negotiated in your contract.

Laura: I think they initially offered me 50% and I negotiated up to 60%.

Kate: That’s pretty standard. Most US publishers offer 50-50, 60-40, or 75-25 for non-English translation rights. If you also get royalties as part of the publisher’s deal for the translation, those will show up here in this part of your statement when the book starts being sold. You’ll get 60% of whatever royalties the press negotiated for.

Your subsidiary rights sales, whether from audio or translation or whatever, all go toward earning out your advance. They all go into that same pot, and they help you start getting royalties sooner.

And sub rights don’t have to be sold the minute the book comes out. Sometimes they happen later, because every country’s book market is radically different.

Laura: Alright, I think that’s the end of the statement!

Kate: It’s interesting, it always takes me five minutes to get my bearings on any royalty statement, because they all look different. They all basically say the same thing, but just in an incomprehensible way. But as we went through it, it seems so much more straightforward than like the first five minutes I look at it. And this is with me having looked at royalty statements for 20 years! So that’s why I know that they’re incomprehensible to authors without someone guiding you through them.

People should feel free to talk to their editors and agents to have them explain this stuff, because that’s literally our jobs. You might think, oh I’m bothering them, this doesn’t really matter. But really, it’s their job. It might not be the number one thing on their to-do list that day, but they should be able to fit in a conversation about it at some point.

Laura: Do you or your authors ever reach out to publishers between royalty statements to ask about sales?

Kate: Occasionally, but it’s funny because the publisher doesn’t necessarily have robust, up-to-the-minute sales figures that people think they do. They don’t know when those returns are going to come in. They know how many copies they’ve sent to retailers, but they don’t know how many of those copies are in people’s houses and how many are sitting on a shelf in a store but not going to sell.

There are some point-of-sale calculations for large retailers that report information like that (sometimes those are referred to as BookScan numbers — the company is now known as Circana). These numbers may or may not accurately reflect your book sales, depending on the places where your book is sold. Some retailers don’t report to BookScan.

Some publishers have author portals where you might be able to see current information. But you might also just be able to download your last royalty statement. It varies by publisher. If your book is sold on Amazon, you can sign up for Author Central which I believe allows you to see Amazon sales information. Only the author can do that, so I can’t do it as an agent.

Laura: I should probably set mine up.

Kate: I’ve heard from publishers not to mess with the marketing part of your Author Central page. But yeah, I would go set it up for yourself because there might be a lot of information in there that you can use.

Laura: Good advice. Is there anything else you think authors should know about royalties and advances?

Kate: There is no “good advance.” Across the board, there is no one number that is good or bad. What is small to one person might be huge to somebody else. There have been some links between large advances leading to large marketing investments on the publisher’s part, and maybe that’s true sometimes, but its not exclusive. Just because you got a smaller advance doesn’t mean you will get zero support from your publisher. There are different factors that play into marketing and they’re not equitable, because it’s not a meritocracy.

Try to keep your eyes on your own paper, because comparing your stuff to somebody else’s is only going to make you sad. Somebody else is always going to get more money than you, and somebody’s book that you hated is going to sell a lot of copies.

My other final tip is to ask questions when you don’t understand something about money regarding your book. And don’t feel bad if all your royalty statements look like gibberish, because that’s what they look like to everybody, even us in publishing, until we sit down and look at them more carefully.

Laura: Thank you, Kate!

I hope you found this conversation helpful. Please feel free to share it with your author friends and save it for the next time you have to figure out a royalty statement for yourself.